This review will appear in a future issue of the journal The Historian. The editors encouraged me to publish it here in advance, with the caveat that editorial revisions may cause the final version to differ from this one (though probably not substantially).

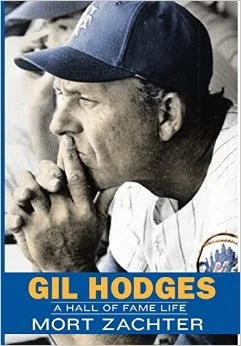

In Gil Hodges: A Hall of Fame Life, author Mort Zachter strives to make a case for why Hodges, the late Dodgers All-Star and Mets manager, deserves induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. As his subtitle suggests, Zachter builds his argument not only on Hodge’s statistical accomplishments but also on his intangible qualities of character and leadership. The celebratory biography that emerges from this effort makes a compelling case for Hodges as a Hall of Famer, but may not be of interest to historians unless they are particular fans of the so-called golden age of New York baseball from the late 1940s through the late 1960s.

Hodges was a vital member of the post- World War II Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers teams that dominated the National League, winning nine pennants and two World Series between 1947 and 1959. Hodges provided those clubs’ most consistent source of power hitting and playing widely acclaimed defense at first base. He went on to manage the Washington Senators and New York Mets during the 1960s, transforming perennial losing cultures in both places and unexpectedly winning a World Series with the “Miracle Mets” in 1969. As Zachter notes, “Hodges hit more home runs in his playing career than anyone else who also managed a World Series-winning team,” and this combination of achievements combined with his sustained high level of play seems to legitimize Hodges case for the Hall of Fame. (xiv)

Zachter capably chronicles Hodges’ career achievements, but his argument that the Hall of Fame (or readers) should consider his subject’s character is less persuasive. He invokes the “legend” of Hodges and proclaims him the “conscience” of the Dodgers but never clearly explains these labels. (xiv, 82, 103) Hodges supported Jackie Robinson during the integration process and mentored younger teammates such as Don Drysdale. (62, 174–79) Yet he also occasionally treated rookies such as Dick Williams roughly when they refused to respect off-field privileges of seniority, and he struggled as a manger to relate to young players and writers who challenged his authority. (104, 223)

Such contradictory examples could result in in a well-rounded portrayal of a notable postwar ballplayer, but Zachter lacks an analytical framework that articulates why readers should care about the life of this very good athlete and decent if not clearly exceptional man. Recent biographers of Hank Aaron and Ty Cobb have used their subjects to offer more expansive cultural insights; Howard Bryant explored Aaron’s career in the context of the collapse of the Negro Leagues and the pressures African-American players faced in the immediate aftermath of Robinson’s trailblazing career, and Charles Leerhsen reexamined Cobb’s reputation as a racist in order to prod readers to recognize the influence of public memory on the formation of such legends. Zachter, though, focuses so tightly on Hodges’ life that no broader relevance emerges from his story. For baseball fans, that may be fine. Most historians probably will want to explore elsewhere.