Photograph courtesy of the High Point Historical Society, High Point Enterprise Collection

This piece originally appeared in the February 15, 2016 edition of the High Point Enterprise.

Last week was the 56th anniversary of the beginning of the Woolworths sit-ins here in High Point, North Carolina. Inspired by the actions of four college students from North Carolina A & T, who had launched a similar protest ten days earlier in neighboring Greensboro, twenty-six 14 to 18 year olds initiated what appears to be the first U.S. civil rights sit-in led by high school students. Accompanied by their mentor Reverend B. Elton Cox (one of the original thirteen Freedom Riders) and Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, these students marched the mile from all-black William Penn High School to the Main Street store, where they asked for and were refused service. Their actions that day instigated a three-year process that ultimately led to the desegregation of the city’s lunch counters in 1963.

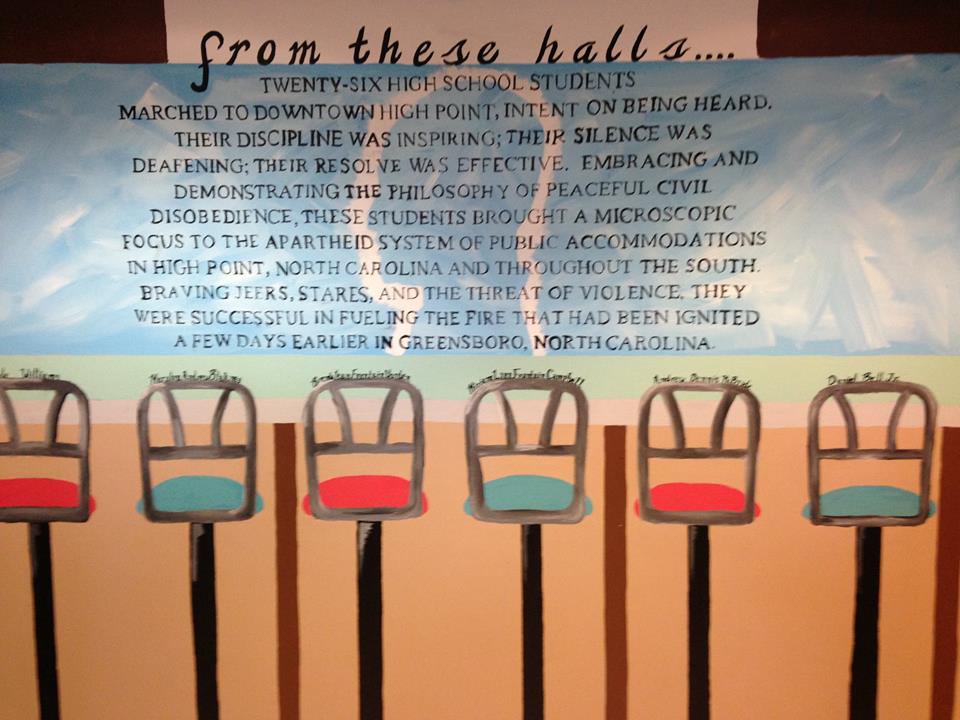

The High Point sit-ins are less well-known nationally than their Greensboro counterparts, but in this area they receive a variety of commemorations every year. In the past, students at Penn-Griffin School for the Arts (which stands on the site of the former William Penn High School) have marked the February 11th anniversary by retracing the march that occurred in 1960. A prayer vigil occurs yearly at 4 pm, the exact time the students entered the store, and the February 11th Association holds an annual banquet each year to celebrate the occasion and raise money for nonviolent education for high school students. This year, Penn-Griffin held an emotional ceremony unveiling a mural celebrating the sit-ins and honoring the students who participated.

These honors and memorials are richly deserved. The bravery of those students who peacefully demanded their rights in the face of not only angry store employees and police inside the store, but also a wrathful mob that pelted them with snowballs filled with needles as they marched back to William Penn, is both extraordinary and inspiring. At the same time, such honors (like the annual lovefest that surrounds Martin Luther King Day) fit neatly into a narrative that media outlets and the majority of Americans find easy to accept — that of a courageous underdog standing up peacefully in the face of a vague and distant form of tyranny. Every TV station in the region sent a truck to cover the unveiling last night because they know it’s a heroic story that aligns with the racial messages of progress and hope that their viewers want to hear.

Partial image of the mural unveiled at Penn-Griffin School for the Arts on February 10th

The unveiling ceremony was moving and important, but during a week when Cam Newton and Beyoncé were vilified widely for diverging from such easily digestible narratives and a year when the simple phrase Black Lives Matter has come under fire from Democratic and Republican politicians alike, such celebrations don’t feel sufficient. We need to do more than celebrate the heroic; we need to grapple with the mundane.

The William Penn Project, a collaborative endeavor dedicated to exploring and publishing the history of William Penn High School, is one example of what such grappling might look like. Our students examine the civil rights activism that occurred at the school throughout the 1960s, but they also explore the daily lives of students in the classroom, on the playing fields, at afterschool jobs, and at home in their neighborhoods on the south and east sides of High Point. What was it like to grow up in a Jim Crow educational system in which only white students got free transportation to school, new textbooks, and guaranteed money for extracurricular activities such as the yearbook and school newspaper? There are lots of individual memoirs about growing up black in the Jim Crow South, but institutional histories that address these and other issues confronted by legally segregated black schools remain shockingly rare. Without better knowledge of the systemic inequities that the High Point 26 and hundreds of thousands of Africa-American children just like them experienced on a daily basis, the prevailing narrative that marginalizes the vast majority of their stories is never going to change. Rewriting the history of High Point and of the nation in a way that respects and values their experiences might be the greatest honor we can offer to those students from 56 years ago who wanted to change the world.